Can I put my savings in Euros, please?

I finished The Untied States of America : Polarization, Fracturing, and Our Future by Juan Enriquez last night.

The book opens with and revolves around the very thought provoking question, "How many stars with the U.S. flag have in 50 years?" Most Americans would respond "fifty, of course" without any thought. Mr. Enriquez spends the remainder of the book providing insightful examples of how other countries have 'untied' (his term for the breakup of a nation into smaller, independent parts) and lines along which and reasons for the U.S. to 'untie.'

Alaska and Hawaii became a states in 1959. The ensuing 47 years make up the longest period in American history without the addition of a additional states. No American president has ever had the same flag fly at his swearing in as was flying the day he was born. Knowing this, the author provides examples of new stars that could be added and stars that could be lost in the next 50 years and beyond.

First, stars that could be added. Aside from Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and other territories already under U.S. control, there are a number of foreseeable situations in which the U.S. could gain territory currently under the control of another nation. Quebec has a long history of seperatist sentiments and has only narrowly failed to come up with enough votes to 'untie' Canada. Should this happen, there are circumstances that could result in new states.

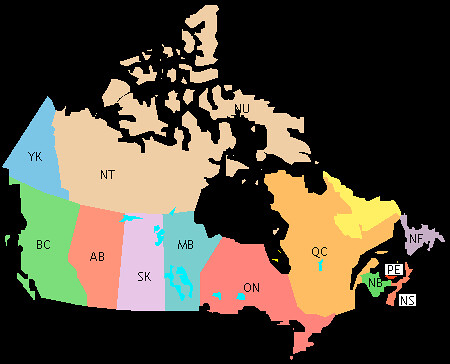

Quebec is centrally located. (The orange province labeled 'QC') It would effectively cut Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Prince Edwards Island, and Nova Scotia off from the rest of Canada. Some of these provinces only became provinces after WWII and considered either independence or being a part of the United States at that time. If these provinces were to be cut off from the rest of Canada, the rich western part and the industrialized areas in Ontario, it is conceivable that they could be added to the United States.

Similar things could happen on the southern border. A great deal of the Baja Peninsula is owned (in trust) by Americans. Its economy is far more connected to California than it is to Mexico. Should any sort of political upheaval break up Mexico, Baja especially, along with other border areas could either form an independent 'transition' nation on the Mexican-American border or seek American statehood.

Admittedly, the concept of Canadian territory becoming part of the U.S. seems more likely. Many Americans consider Canada a sort of '51st state' anyway. The sad fact is that the population of these coastal territories would have a better chance at statehood due to their largely Northern European ancestry...

Perhaps more likely, given recent trends in Europe, Asia, and Africa, is that the United States would loose stars.

Vermont, Hawaii, have active secessionist movements. Other states, especially those along our southern border, are both culturally dissimilar to the majority of America and were formerly part of a nation that shares that culture. Mr. Enriquez notes that all across Europe, borders have a tendency to 'snap back' even if those borders had been erased centuries ago. (Increased independence for Wales and Scotland, for example.)

The 'Blue State vs. Red State' divide is also examined. The author observes that when populations within a nation become sufficiently self identifying and unintegrated, splits often occur, but not in the way that might seem most likely. Given that The South has already seceded once and makes up a significant part of 'Red America' one would think it most likely for the 'Red States' to secede again. Mr. Enriquez contends that this isn't the case. Most secessionist are by the more eoonomically viable portion. When a population or region becomes convinced that the could be richer by themselves, they secede.

The North East and West Coast is certainly more viable than the remaining states. 'Blue' states are overwhelmingly tax 'givers,' receiving less federal money than they pay in taxes. 'Red' states are almost exclusively 'takers.'

If divisive politics continue to drive 'Red' and 'Blue' further away from each other, an Untied States of America could easily result. As a nation, we've existed for only 5 lifetimes. The author reminds us that there is no reason that The United States of America must exist in the future.

As economies become increasingly knowledge based, small nations (cough, cough, South Korea, cough) can easily compete with larger nations. Shedding regions that don't 'pull their weight' becomes an increasingly attractive option. The Northern Italians want to ditch their Southern portion, the Western Canadians would like to stop paying for their Eastern Provinces, Northern Mexico would be better off discarding the south. It is not unlikely that if cultures and economics continue to diverge that there may come a point when parts of the United States would seek to disentangle themselves from less productive parts of the country.

Enriquez touches on many other important topics including the problems associated with increased national debt and the emergence of Native Americans as important players in politics. These tribes, ignored for so long, are beginning to establish their rights as sovereign nations, a position recognized by treaties signed but forgotten.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of this book isn't even what's printed on the page - it's HOW its printed on the page. There are no paragraphs. The entire work is an assembly of short declaratory sentences (or less) arranged, spaced, and sized for maximum impact. Charts and graphs abound. It is clear that the author conceived the entire page, not just his words. This probably bothers some people (it certainly did for at least one reviewer on Amazon.com) but I find it not just readable but incredibly informative, cluing the reader in to the author's ideas about what's important and how certain concepts mesh together or can be juxtaposed for power and insight.

I highly recommend this book, especially as a gift to moderates and center-right types. It exposes the faults in the programs and agendas in the modern Conservative movement without sounding like, or really being, a broadcasting of progressive talking points. It accentuates that Progressive positions are better not (only) for their philosophical and ideological content, but because they will be more effective. American pragmatism at its best.

No comments:

Post a Comment